Domestic abuse in rural communities

The issue of domestic abuse in rural areas

We launched our national rural crime campaign last week. One element of the campaign focuses on rural domestic abuse. Within rural communities, victims of domestic abuse (both male and female, young and old) are often isolated, increasingly unsupported and left feeling unprotected - with abuse lasting, on average, 25% longer than in urban areas*

Former Women’s Aid Chief Executive Polly Neate talks about the issue of domestic abuse in rural areas and the importance of community awareness of this crime.

For many women in rural areas, their nearest specialist can be up to two bus-rides away from their home. If her partner controls access to a car, denies her petrol money, checks her mileage, or demands an explanation every time she leaves home, that distance can mean a woman is simply unable to get to a specialist support worker.

Similarly, in a small community where a new vehicle would be noticed, a woman cannot be safely visited by a support worker on a regular basis, in case word gets back to the perpetrator that a strange car has been seen at their home.

Isolation in rural communities

Isolation can trap women anywhere. But in rural areas, the social isolation can be compounded by geographical isolation and the perpetrator can be protected by the small size of the community. If your neighbours have known you their whole lives, they simply may not suspect you could be capable of domestic violence.

There may be an assumption that domestic violence is an inner-city problem, confined to lower socio-economic or ethnic minority groups. And a woman can feel very vulnerable seeking support from her neighbours, the local police, or her family doctor where she may become the subject of local gossip.

“When he began breaking into her house to assault her, she didn’t report it to the police as she thought the bullying would get even worse for her children.”

The reality of social isolation in rural communities

Where women feel they can’t turn to the police, the results can be especially dangerous.

In one case, a woman who lived in a small rural community didn’t want to call the police about her violent ex-husband because she worried about her children. She said that she hadn’t called the police during their marriage because the whole street would have seen, and the local officers knew her husband.

Then when she divorced him, many of her neighbours felt she was treating him unfairly, and her children started to be bullied at school. When he began breaking into her house to assault her, she didn’t report it to the police. She thought the bullying would get even worse for her children, if people thought she was experiencing violence or, worse, making false allegations.

What can you do about domestic abuse in your community?

In addition to good quality policing, rural communities can benefit from a broad awareness of domestic abuse issues, and a sensitivity to the power dynamics behind it.

If women experiencing geographical isolation are not to be disproportionately impacted by cuts to specialist services, it is vital that their communities are able to help them. That help could mean neighbours who can recognise the symptoms of domestic abuse, believing women who report violent or controlling behaviour, or maintaining friendships.

If you think a woman is a victim of this crime you can provide a lifeline if she’s ready to take it; and challenge the stereotypes and myths about domestic abuse.

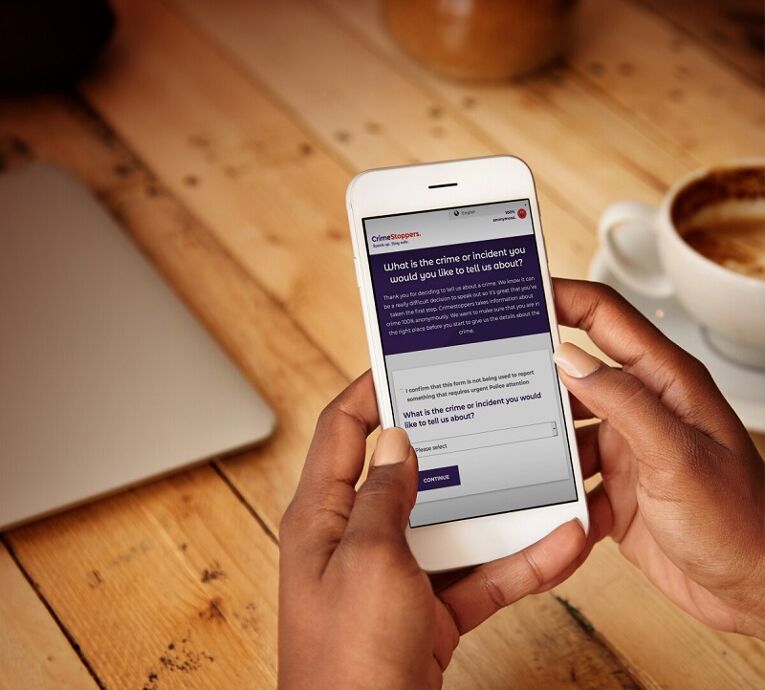

You can give information about crime 100% anonymously through Crimestoppers on 0800 555 111 or through our Anonymous Online Form.